Sprache

Typ

- Buch (6)

- Wissenschaftlicher Artikel (2)

- Interview (0)

- Video (0)

- Audio (0)

- Veranstaltung (0)

- Autoreninfo (0)

Zugang

Format

Kategorien

Zeitlich

Geographisch

Nutzerkonto

Digital ‘Multitudes’?

Dystopian Prologue

Digital ‘Multitudes’?

The ‘cyber’-culture of the 1980s and 1990s was more than just a pop phenomenon: though, on the one hand, it was a product of science fiction novels like William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984), films like The Matrix (1999) and early electronic social media like The Well, it was also theorized academically within cultural studies, media studies and the social sciences of the time. In cyberfeminist texts such as Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto (1983), Sadie Plant’s Zeros and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture (1997) and N. Katherine Hayles’s How We Became Posthuman (1999), the hybridization of the ‘real’ and the ‘virtual,’ of bodies and machines, became a central concern. Against the backdrop of cyberculture and gender studies, cyberfeminism, declared by the Australian artist collective VNS Matrix in a 1991 manifesto, viewed the technical and cultural disruption of digital information technology as a way to undermine traditional gender relations. In the mid/end 1990s, just as the World Wide Web was becoming a mass medium, the term “network” increasingly began to supplant “cyberspace.” The framework for this was provided by sociologist Manuel Castells, who in 1996 announced “the rise of the network society.” Within art, this found expression in two opposing currents: on the one hand, there was the older, highly subsidized and institutionalized media art originating within the sphere of academic computer music studios and media labs, who didn’t quite know what to do with the decentred, participatory medium of the internet, which at the time still had very limited multimedia capabilities. On the other hand, there was the younger ‘net culture’ and net art, which set out on the path forged by The Well, working outside of the institutional context and making use of comparatively simple technical means.

With his introduction to the concept of “new media” in 2001, artist and media theorist Lev Manovich established a conceptual structure that could accommodate both the work of institutional media labs and activist net art. Manovich’s criteria of “numerical representation,” “modularity,” “automation,” “variability” and “transcoding” yield a cybernetics that can be used to describe technical as well as cultural and political processes. These five key principles can be applied to analyze a generative electronic music composition programmed with MAX/MSP or Pure Data, they can analyze the interplay between the various open-source softwares forming the technical infrastructure of modern web sites, like the Linux operating system, the web server Apache and the database management system of modern websites MySQL. The five terms can also, however, be applied to describe the process through which a news image becomes a parodically animated GIF that is varied dozens or even hundreds of times as it spreads across social networks, or a cyberfeminist intervention such as the one performed by artist Cornelia Sollfrank at the annual Chaos Computer Club convention in 2000, in which a fictional female hacker spoke via video and computerized voice to a misled hacker audience.

Digital multitudes emerge, if one follows this line of thinking, at the point where technology and identity intersect along cybernetic criteria like those proposed by Manovich. Whether it is data files or identities that are made variable and transcoded makes no fundamental difference from the viewpoint of this theory. And it is at this point, where postmodern cybernetics from Haraway to Manovich overlaps with the classical cybernetics of the 1940s and 1950s, which, far from celebrating the promise of artistic freedom, is rooted in a brutal mechanistic and behaviouristic worldview. All postmodern notions of “fractal” subjectivity (Jean Baudrillard), “collective intelligence” (Pierre Levy), “multitudes” (Negri/Hardt), “peer-to-peer society” (Michel Bauwens) and the popular non-fiction bestseller idea of the “wisdom of crowds” are all based on the assumption that networks constitute a structural break with hierarchy and one-dimensional models of stimulus/response and sender/receiver. They thus assume that the network society functions in a “rhizomatic” way, in the sense laid out by Deleuze and Guattari, and that its undercurrents have always been inherently rhizomatic.

These ideas were much more provocative for the field of fine art than they were for the humanities and cultural studies, which since the 1980s had already largely digested the critiques of authorship and the work given by Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes. In the institutional art world, ‘multitudes’ and ‘network culture’ collided with an aesthetic tradition centred around the individual artist, the work and the signature. For the most part, this tradition had remained intact since the Romantic era and persists as the transactional basis dictated by the art market. Since the 20th century, politically radical avant-garde art had attempted to alter these conditions: Russian Constructivism, for example, with its concept of “productivist art,” and Fluxus, which George Maciunas originally conceived of as a collective label to which Fluxus artists would transfer their rights. The implications of “network culture” and the “copyleft” of the free software movement around GNU and Linux were similar, yet they functioned on a global scale and on a decentred, self-organized basis.

Netromanticism

Despite clashing with the art system’s legacy of romanticist genius aesthetic, network, ‘rhizome’ and ‘multitude’ are themselves romantic concepts, seamlessly connected to the ‘folk’ romanticisms of the 19th century. The fairy tales collected by the Brothers Grimm, von Arnim’s and Brentano’s Des Knaben Wunderhorn and the 19th century philological construction of national romantic epics such as the Nibelungenlied: all of these are ‘network’ products of a nameless ‘multitude.’ Romanticist philology also provides a blueprint consisting of Michail Bakhtin’s literary theory of carnivalesque folk culture, the post-structuralism of the French Tel-Quel group in the 1960s (via Julia Kristeva’s early essays on intertextuality) and, stemming from this, Pierre Levy’s thought figure of collective (media) intelligence.

In his life-long campaign to “drive the human out of the humanities,”media theorist Friedrich Kittler drew a crucial critical link between postmodern cyber-network utopias and the use of computers, algorithms and electronic communication as military-industrial structures of control. It is striking that this was done as early as the start of the 1990s, at a time when the internet’s image in popular culture was still summarized by a cartoon of a dog chatting on a PC with the underlying caption, “On the Internet nobody knows you’re a dog.” Two decades later, in the age of ubiquitous user registration and the aftermath of Edward Snowden’s disclosures revealing the total surveillance of all activity on the net, this once commonly held notion can only be understood as a historical document. The call to be “saboteurs of big daddy mainframe,” as communicated in VNS Matrix’s “Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century” (1991), reads, nowadays, as devastated romanticism.

Anonymous and Memes

Today, the “Anonymous” movement embodies the remains of this romanticism, not least because it is based on a retro recourse to this period of the 1990s, adopting the pop cultural image of the heroic hacker-outlaw as seen in Hollywood films such as Hackers (1995) and The Matrix (1999). Since the “Occupy” movement in 2011, the face of Anonymous – a mask worn by the English revolutionary Guy Fawkes in the graphic novel (and 2005 Hollywood film) V for Vendetta – has become a global sign of protest (fig. 1). With it, the romance of genius and individual heroism still embodied by Che Guevara’s face during the protest movements of the 1970’s dissolves, and is replaced with the folk romanticism of a collective, anonymous identity.

Fig. 1

Guy Fawkes-mask,

www.guyfawkesmask.org.

In 2012, philosopher of technology, Occupy-demonstrator and net activist Harry Halpin wrote that “the political power of Anonymous cannot be separated from its strange world of memes, a unit of self-replicating culture originally theorized by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins.” In his 1976 book The Selfish Gene, Dawkins applied the Darwinian principle of “survival of the fittest” to genetics. From this, he derived a “mimetics” that sought to explain the cultural dynamics of information-transfer in terms of genetic replication and evolution. As media theorist Wendy Chun has commented, Dawkins’s ideas resemble the “self-replicating automata” imagined in the 1940s by John von Neumann, one of the founding figures of computer and information science. Yet Chun points out that while von Neumann only ascribed such self-replication to hardware, Dawkins privileges “a concept foreign to von Neumann in 1945: software.”

Independently of Dawkins – and as early as 1970 – William S. Burroughs’s Electronic Revolution formulated a poetics of the word as self-replicating virus. Burroughs, too, couples the viral sign with electronic media technology: specifically tape recorders, onto which messages can be recorded, reassembled and played back into public space (a process envisioned as a fiction of media revolt in the German film “Decoder,” from 1984, which also features Burroughs in a guest role). He insists, therefore, that his idea of the word as virus be taken literally and not as metaphor. Like his artistic partner, the painter and experimental poet Brion Gysin, he made reference to the montage procedures of the Dadaists and Surrealists, and, beyond that, to pop culture, contemporary politics (such as the Watergate scandal around Richard Nixon) and occult parasciences. When it comes to a historical poetics and theory of internet memes, Burroughs’s ideas have much more to offer than the deterministic arguments of Dawkins. In any event, the relationship between what “meme” means within popular internet culture and how it is defined by Dawkins is one that is loosely rooted within colloquial speech and should not be taken all too literally within media theory.

As Linda K. Börzsei has convincingly argued, “emoticons” – smiley faces made using text characters – were the first net culture memes in the structural sense of an infectious, widespread information unit consisting of text and image. Their use dates back to 1982. The contemporary version of the internet image meme, also called the “image macro,” emerged between 2005 and 2008 in the form of “LOLcats” and “Advice Dogs.” The website Knowyourmeme.com documents all known memes and traces their history. It is thus an indispensable reference for the philological study of internet meme culture.

Essentially, today’s internet memes are grotesque pictorial jokes that are spread and varied by internet users. They are the most prominent example of a contemporary popular culture that is a genuine product of the internet and its users. Though they draw from images found in classical mass media, such as the news, film, television series and comics (thereby adopting a strategy already familiar from Dada and Pop Art), the resulting images are anonymous creations that are most often digital variations of already existing memes. In this sense, they perfectly fulfill Manovich’s “new media”-criteria of modularity, variability, transcoding and numerical representation.

The structure of today’s image memes, which has by now become standardized and genre-typical, resembles the structure of Renaissance emblems. The internet meme perfectly echoes the emblem’s tripartite division of inscriptio (heading), pictura (image) and subscriptio (caption). In the meme, however, the image-content usually fully fills the format and the accompanying text is not offset, but rather placed directly on top of the image using thick, white type (Microsoft’s Impact font, with a black drop-shadow). The meme’s heading introduces a joke or funny question that, when read in combination with the pictorial motif, generates a tension that is subsequently resolved in the punch line at the bottom of the image. An excellent historical analogy can thus be made between the meme and internet joke culture, and the image emblem and the rhetorical joke (concetto or argutia), a form theorized by Jesuit rhetoricians like Emanuele Tesauro as early as the 17th century.

Ever since the moment internet-memes began migrating from subcultural forums to popular mass media outlets like the American news aggregator Reddit.com, they have arguably become the most powerful phenomenon of contemporary pop image culture. Today, in 2014, they are nevertheless little-known outside of the English-speaking world, partially due to the fact that their slang, puns and cultural references overtax the competence of most non-native speakers. Anyhow, the roots of internet-meme culture do not come from European but from Japanese visual culture. This is apparent when we take one of the most well-known memes, Y U NO guy, (fig. 2) as an example. Here, a face appropriated from the Japanese science fiction manga Gantz is cut out, flipped horizontally and combined with the text: “I TXT U / Y U NO TXT BAK!?” (corrupted English for “I wrote you a text / You don’t text me back!?”). This image and its accompanying text fragment, “Y U NO,” has taken on a life of its own, circulating as what are by now thousands of meme-variations.

Fig. 2

Y U No guy-Meme, 4chan.org, 2009.

Popular since 2005, the Mudkips (fig. 3) meme is based on a Pokemon cartoon character named mudkip, accompanied by the caption: “so i herd u liek them” (corrupted English for “so I heard you like them”). In its original form, it subscribed to an older visual format taken by the internet meme: the image placed inside a black matte, a large caption in uppercase Times New Roman font, and below this, the punch line set in small, lowercase Microsoft Arial.

Fig. 3

Mudkips-Meme, 4chan.org, 2005.

Like this meme’s image motif, its initial medium of distribution – an imageboard – originates from Japanese pop culture. Imageboards are technically simple websites onto which users post images and short text messages. Other users are then able to react to these postings with images and short text responses. Originally part of the fan culture around manga and anime, these sites functioned in a way similar to the first self-published fanzines (later called “zines”) in 1940s American science fiction culture: initially fan media, they later spun out to become an independent form of DIY-media.

In the Encyclopedia Dramatica, founded in 2004 and appropriating the form of Wikipedia, imageboard and meme culture builds a textual monument to itself. This results in a countercultural work of the same historical importance as the principia discordia, first published 1965, and the anonymously and collectively written Jargon File of hacker culture from 1975.

4chan

Encyclopedia Dramatica and imageboards are the two originary media of meme culture and the Anonymous movement. Today, the best known and widely used English-language imageboard is 4chan.org, established in the USA in 2003 and modelled after the Japanese Futaba Channel (also known as “2chan”). The analytics website Alexa.com ranks it as the 715th most popular website worldwide and the 306th most visited within the USA. Unlike practically all other conventional internet forums and social media sites, 4chan requires neither login nor registration. Every user, that is to say, anyone who posts images and comments on 4chan’s subforums which are called “boards,” remains anonymous and operates indiscriminately under the username “Anonymous.” While most 4chan boards have names associated with manga culture, from “anime” to “yuri” (lesbian-themed manga), the random /b/ board forms the actual core of the site and is regarded as “the place where the Internet goes to vomit after a late night out.” The material shared on /b/ consists mostly of obscene, grotesque pictures and commentary. This board is both a point of origin for the majority of memes, as well as the birthplace of internet-meme-culture on the whole. The mudkips-meme, for example, first appeared here in combination with a “copypasta” grotesque (meaning a text copied from the internet, slightly rewritten and then pasted into a post) about a schoolboy’s sexual encounter with the mudkip character from Pokemon; hence the meme’s caption, “so i herd u liek them.” Through “Rickrolling,” the first popular video memes came into being through 4chan in 2007: these were deceptive videos placed in online portals like YouTube, always ending with an excerpt from Rick Astley’s original pop music video, Never Gonna Give You Up (1987).

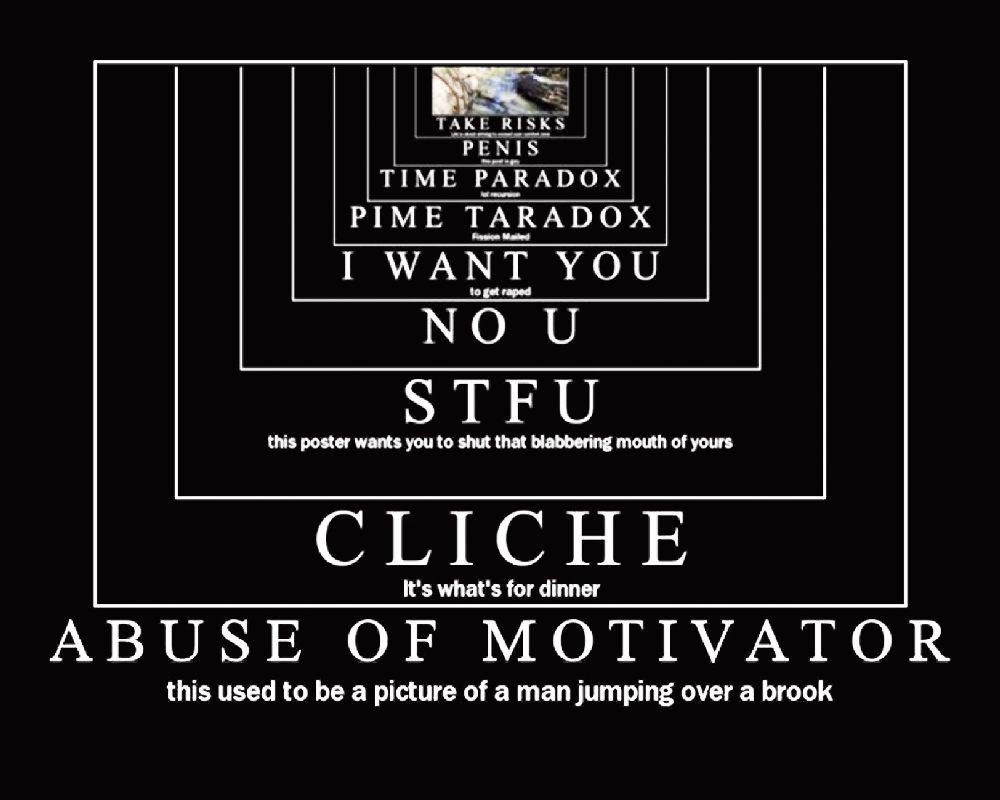

Over the years, the codes, variations, external references, internal cross-references and jargon of 4chan memes have become more complex. Thus, as often occurs with subcultures, they are not easily accessible to outsiders. The best examples of this are self-reflexive memes, some of which are, without a doubt, conceptual art (fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Complex meme, 4chan.org,

ca. 2013.

Anonymous as a Social Movement

The origin of the Anonymous-movement lies in the simple fact that the defaults of 4chan’s website ensure that all users are anonymous and contribute collectively as ‘Anonymous.’ Anonymous is a product of 4chan. Yet it first manifested as a movement in 2008, when the Church of Scientology filed a lawsuit against YouTube and other websites in response to a leak of a video of actor Tom Cruise praising the Church. (This story is particularly ironic, since both Scientology and Burroughs – who, as he reports in The Electronic Revolution, was an intermittent member of the Church – share a belief in language and communication as mental programming. In this, they refer to Polish-American semantic scholar Alfred Korzybski, who described the process by which linguistic expressions assume a separate existence that comes to overshadow their referent, in the form of, say, stereotypes, as a societal problem. The meeting of Scientology and 4chan is thus a collision between two meme-obsessed subcultures.) In the anti-Scientology protest organized via 4chan’s random-board, Anonymous became a collective identity, and the mask worn by the English Catholic revolutionary Guy Fawkes became its memetic face.

The historical figure of Guy Fawkes was involved in an early 17th Century plot to assassinate King James I. Prior to the date of his official execution, he took his own life. To this day, Guy Fawkes Night, celebrated in British folk culture on November 5, commemorates Fawkes through a ritual burning of straw effigies bearing his face. In 1982, British author Alan Moore cast Fawkes as the hero for his comic series, V for Vendetta. This graphic novel projected the Thatcherism of the 1980s into a fascist dystopia of 1990s England; a world resisted by the violent anarchism of the masked Fawkes. The filmic adaptation of V for Vendetta (2006), written and produced by the Wachowski siblings, who had previously directed The Matrix, transfers the dystopia of the graphic novel into the 1920s. In its concluding scene, a self-organized crowd of thousands of Londoners wearing Guy Fawkes masks march to Parliament. Analogous to this, the Anonymous protests, dubbed “Project Chanology,” began as international, masked street demonstrations in front of buildings and promotional booths belonging to the Church of Scientology.

In the five years between 2008 and 2012, a period reaching from Project Chanology to the mass popularization of the Guy Fawkes mask through Occupy, contrasted with the infiltration and destruction of an important hacker contingent of Anonymous by the FBI. Anonymous and imageboards formed an aesthetic and political countercultural movement whose reach and strength could be compared to hippies in the 1960s/70s and punk in the 1970s/80s. However, this movement also makes evident the extent to which both popular culture and counterculture have departed from their former key media – music and fashion – and have become a phenomenon of the internet. Shifts within image culture are also apparent: while hippies and punks asserted their individuality, difference and antagonism through public displays of outward appearance, Anonymous strives for difference through the veiling of individuality and aspires to freedom through non-identifiability. Anonymous repeats the Rock’n’Roll Swindle articulated and cynically embodied by the Sex Pistols, who took up signs designed by Malcolm McLaren, Vivienne Westwood and Jamie Reid. Guy Fawkes’s face is the intellectual property of Warner Brothers, who collect the licensing fees for each mask that is sold.

Precursors

Due to the huge success of Anonymous, it is tempting to assume that the decentralized, collective use of a name or an identity is a phenomenon arising purely from the internet. This sort of thing has, however, been around for much longer. In early 19th century England, the fictional “Captain Ludd” became a collective figure for the Luddites, a workers’ movement opposed to the Industrial Revolution. Despite the contradiction between the Luddite’s attack on the machine and the hacker’s love thereof, there is a striking similarity in iconography, historical mythology, swarm logic and folklore of resistance between the Luddite philosophy and Anonymous – Captain Ludd and Guy Fawkes.

In the 1920s, Marcel Duchamp and surrealist poet Robert Desnos invented the identity of Rrose Sélavy, a wordplay on “éros c’est la vie.” Both artists created individual works that were attributed to this name. One such work by Duchamp was a series of photographs (shot by Man Ray) of Duchamp dressed in drag as Rrose Sélavy. In 1978, artist (and former art school professor) David Zack invented “Monty Cantsin,” an identity meant to function as an “open pop star,” who could be used collectively by various artists for independent performances. Eight years later, in a letter to Berlin subculture activist Graf Haufen, Zack wrote, “the idea that people can share their art power is a very good one I think. My own understanding is that it is about sharing, about bash: cooperation between people, putting egos and tempers aside. Though not always seeming so.” His last sentence refers to the use of Monty Cantsin’s identity during the 1980s, which was indeed often overshadowed by ego conflicts, for example, by performance and video artist Istvan Kantor and author Stewart Home.

Zack was one of the primary figures of Mail Art, a postal network introduced in his 1973 Art in America article, “On the Phenomenon of Mail Art.” He was also one of the early correspondents for FILE, a magazine published by the Canadian artist collective General Idea. As part of an open network of communication whose participants largely operated under pseudonyms and appeared in costume on the magazine’s cover pages (fig. 5), FILE anticipated many aspects of the Anonymous movement. This included the recycling of images from popular culture and mass media, a tactic already at work in the magazine’s title and design which imitated the illustrated journal, LIFE. It is safe to say that from today’s point of view, the early issues of FILE can be read as predecessors of imageboards from within the field of experimental art.

Fig. 5

Cover of FILE magazine,

Mr. Peanut Issue, 1972.

Formed in Italy in the 1990s, the Luther Blissett Project used the collectively shared name of a real-life soccer player in order to stage media pranks and practice political activism. Like the Luddites before them and Anonymous after, the members of the project convened under an iconic phantom portrait (fig. 6).

Fig. 6

Luther Blissett, anonymous picture, 1994.

The founders of the Luther Blissett Project were fully aware of their predecessors, including the Mail Art and Monty Cantsin, and indicated them in their manifestos. Yet, Luther Blissett was not essentially an artistic project; it was, instead, focused on political activism that was directed primarily towards the mass media and made visual reference to pop culture. In these ways, it historically anticipated Anonymous. Politically, the project was linked to the undogmatic Italian leftists assembled around the “a/traverso” collective and the 1970s radio broadcast, Radio Alice. The shared identity was referred to as a “condividuality,” in which Luther Blissett functioned as a collective phantom and a “multiple single.” A decade later, during the student strikes of 2008, Anna Adamolo, a fictive Italian minister of culture, was launched to become the collective identity of the protest.

Dystopian Perspective

Considered in terms of their historical sequence – from Rrose Sélavy to General Idea, Monty Cantsin to Luther Blissett, all the way to Anonymous – the use of collective identities has become increasingly detached from contemporary art (fig. 7).

Fig. 7

Rrose Sélavy-variation by John Cates, 4chan.org, 2010.

Anonymous is the first avant-garde movement that exclusively draws from popular culture and is informed by both Anglo-American and Japanese visual culture. (Meanwhile, in Western contemporary art, art-world-navel-gazers like Liam Gillick are considered to be critically cutting edge.)

However, the retrospective view of art history also relativizes Anonymous along with its imageboard- and meme-culture. It turns out that these are not just products of a year-zero in digital network culture and cybernetic “multitudes.” All overly-simplified, media-ontological explanatory models claiming new media as the autonomous source of dispersed authorship and “fractal” identity are thus invalidated. Yet, what the historical predecessors of Anonymous also make clear is that the introduction of the Internet finally offered the infrastructure necessary for a self-organized movement of collective identity to become a global, mass phenomenon. In this way, the Anonymous movement grew into maturity with a weapon that has since turned against it. Since Snowden’s disclosures, it is clear that hackerdom in the sense of the heroic 90s cyberculture cliché is no longer possible, and neither is an ‘Anonymous’ romp on an imageboard. It comes as no surprise, then, that the hacktivist actions of Anonymous have begun to decline, or – like Operation NSA, which was planned in 2013 – completely fizzle out. The fact that today, Anonymous most often manifests as a sticker or a piece of graffiti in public space, and as a mask worn at a street protest, indicates that this net culture, too, has become post-digital.

- Anonymous

- Digitale Kultur

- Identität

- Internet

- Netzkultur

- Subversion

Florian Cramer

hat eine Forschungsprofessur für Medienwandel in Kreativberufen an der Willem de Kooning Academy Hogeschool Rotterdam inne und ist dort Direktor des praxisorientierten Forschungszentrums Creating 010. Darüber hinaus arbeitet er am Programm des Rotterdamer Experimentalmusik-, -film- und -medienorts WORM mit. Nach dem Studium der Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaften und Kunstgeschichte in Berlin, Konstanz und Amherst/Massachusetts arbeitete er von 1998 bis 2004 als wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Peter Szondi-Institut für Allgemeine und Vergleichende Literaturwissenschaft der Freien Universität Berlin. Cramer schreibt und veröffentlicht über Künste, Experimentalismus,

Informationstechnologie und Politik, regelmäßig auch in dem Fanzine Jenseits der Trampelpfade.

-

Anonymous, imageboards, memes. ePunk des frühen 21. Jahrhunderts

In: Kerstin Stakemeier (Hg.), Susanne Witzgall (Hg.), Fragile Identitäten

What is the current state of the subject and what about the status of its self-image? In contemporary discourses we encounter more and more “fragile identities,” in artistic works as well as in scientific theories, and those are today much less referring to a critique of the concept of identity, but much rather to the relationship those concepts of identity entertain with the overall precarious state of the subject in current social conditions that are characterized by political upheaval and change.

The book Fragile Identities investigates among other things the chances and also the possible endangerments of such a fragile self and asks for the resurging urgency of a contemporary concept of subjectivity. The publication combines international artistic and scholarly contributions, discussions and project documentations in relation to the second annual theme of the cx centre for interdisciplinary studies at the Academy of Fine Arts Munich.

-

9–12

Editors’ Preface

Kerstin Stakemeier, Susanne Witzgall

-

13–20

Fragile Identities and the Question of Cohabitation – Introduction I

Susanne Witzgall

-

27–36

-

37–52

Meticulous Insanity

Emily Wardill

-

53–63

-

64–78

-

79–90

-

91–95

“Fragility is the only thing I really know about me” ABO

Claire Denis

-

96–101

-

102–106

Different Accounts

Sarah Rifky

-

107–116

-

117–127

-

128–134

-

135–143

Nomadic Subjects OPEN

ACCESSRosi Braidotti

-

144–158

-

159–164

-

165–174

The Production of Subjectivity ABO

Maurizio Lazzarato

-

175–181

Munich, 10.01.2014

Jana Euler

-

182–195

Expropriation and Uselessness. Fragile Identities OPEN

ACCESSKerstin Stakemeier

-

196–201

Rosebud/Raking Light

James Richards

-

202–214

-

215–228

-

229–235

The Authors